Our Last Best Act: Planning for the End of our Lives to Protect the People and Places We Love1/12/2022

Mallory McDuff Author, Our Last Best Act: Planning for the End of our Lives to Protect the People and Places We Love After his sudden death in 2005, my father had a natural burial in his neighborhood cemetery—although I’d never heard the phrase “green burial” at the time. When I was growing up, my dad built the prototype of a pine casket, the size of his palm, and my mother kept her jewelry in it.  Caitlyn Hauke, PhD President Board of Directors Green Burial Council International On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Green Burial Council International, I am excited to introduce John Niedfeldt-Thomas, who joined us in June as Chief Association Executive (CAE).  By: Mary Ann Perry Sexton, The Forest Conservation Burial Ground [email protected] www.theforestconservationburial.org Life surrounded us as we approached the grave site with Scott’s body wrapped beautifully in a silk shroud woven with color. Deer walked across the meadow while we watched from the edge under the protection of towering pines and firs. Though this was a reverent affair, the swallows in the nearby nest box maintained their dutiful rhythm of caring for the new lives entrusted to them. The Forest Conservation Burial Ground, Oregon’s first dedicated natural burial ground, had only been officially open for burials for about two weeks when we received the call. She was a friend of the family and was stepping up to offer support in a time of need. The backstory was tragic. Two mid-life and in love sailors adventuring around the world, finding themselves on land (in Miami, FL) to be with family and see what would unfold with the game-changing novel coronavirus. Their paths took a sharp and unexpected turn one morning over coffee when Scott collapsed. A few days later he would be pronounced dead. His wife, Viviane, knew that a natural burial was the choice for them, as was returning to the west coast. After a few email and phone exchanges, the burial was scheduled and travel arranged.

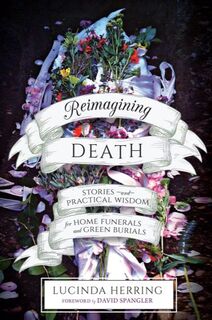

By Holly Blue Hawkins © 15 March 2021 The Rabbi’s voice rang out, singing the words of the 18th century sage Rebbe Nachman, above the wailing of mourners guiding the pallbearers. “All the world is just a narrow bridge….” We paused seven times along the way as if to say, “We don’t want to do this,” then resolutely moved on to fulfill the divine decree “you shall surely bury.” The open grave with mounds of dirt piled to either side seem like earthen wings spread wide to gather this one back into the nest. The opening is hand-carved with care, its floor gently arched to the center so that the lowering straps can be gracefully removed. Within the simple, kosher casket lies a body that has been prayed over, bathed, ceremonially purified with flowing water and guarded. “You are a garden spring, a well of fresh water, a rill of Lebanon….” It has been dressed in the simple, white garments of the High Priest on Yom Kippur, casketed with the utmost care, enveloped in a shroud of natural fiber and (if it was their custom) wrapped in a prayer shawl.  by Susan Greer I had never experienced a natural burial. Then I learned the hard way—firsthand—just how beautiful it is. We could no longer deny that our beloved golden retriever was old. By 2020, Gracie, at the age of 12, had become arthritic, and was growing blind and deaf. Knowing that the end of her life was nearing, we considered a special final resting place for her. The answer, at least last summer, seemed obvious: my parents live in the country, in a home we call “the farm”. There’s a small pond with an island that Gracie loved to swim out to so she could chase the Canada geese. Last August, with heavy hearts, we gathered shovels and dug her grave. We covered it with plywood, hopeful that we’d have more time with her.  by Dina Stander What is a burial shroud? A burial shroud is a wrapping for a deceased being's body. We also call them winding sheets, grave clothes, cerecloth, Tahara, Kaffan. I have learned many words for shrouds since my first personal shrouding experience in childhood, when I wrapped a dead bird in leaves tied securely with long grass before burying it in the meadow. That instinct to protect the remains of the beloved, and to make the body easier to transport for disposition, has many cultural and historical expressions. From ancient art to fine art to photo montages of a modern day pandemic, we are not strangers to seeing images of shrouded bodies. Shrouding customs are practiced in significant world religions and cultures (widely by Hindus, Muslims, and Jews, in African communities, and by some Christian sects), each with its own rules and specifications. No one culture, group, or custom originated shrouding. It is a loving kindness that human beings have shared through collective memory over time.  By Lucinda Herring I almost missed the email that day. Luckily the words “exploring a book project” caught my eye. I had been writing a book over many years about my mother’s remarkable death and home funeral on our family land in Alabama, but I had put it down after a disappointing journey with an agent/publisher. And life happened; I got the opportunity to become a licensed funeral director, to strengthen the work I was already doing as a home funeral and green burial guide, and that work became all consuming. I answered the email from Tim McKee of North Atlantic Books right away, and the rest is history.  by Holly Pruett My father’s death was my first experience of serving as a home funeral guide—I just didn’t know it at the time. In fact, what was missing at the time of his death has been one of my greatest teachers. My father was super fit and healthy, in his early 60s, when he was diagnosed with an aggressive and nearly-always terminal form of brain cancer. He had a six-month prognosis but ended up living for 18 months. I joined my step-mother in caring for him at home, with the support of hospice. Once he exhaled for the last time, strangers arrived with a gurney, zipped him into a body bag, and drove him off for a direct cremation. A few weeks later I was given a portion of his remains and some of the artifacts of his life. Not only was there nothing you would call a home funeral; there was no funeral at all, no memorial. He didn’t want one, I was told—and that was pretty much the end of the story.  by Freddie Johnson The plan for a local conservation burial ground began in 2007 when a friend of mine, Larry Schwandes, shared his discovery that such a thing existed. I was immediately energized by the vision of such a place in our Gainesville, FL community. I suggested as a first step in our action plan that we meet with another friend, Robert (Hutch) Hutchinson, who was the Executive Director of Alachua Conservation Trust (ACT), a local land trust. Hutch was totally supportive of the idea and eager to help.  by Ruth Faas In 1984 my father died suddenly. Coming from a working class family, we had to use the least expensive casket and I instantly thought—“People will think we didn’t love him!” My brother gets frustrated with me when I tell this story, and I understand that—I would never think this of someone else. Yet, we don’t always know what we’ve internalized. |

Call for EntriesWe welcome original content with unique perspectives for the GBC Blog, preferably not previously published. The views and opinions expressed on the GBC Blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the GBC. Submit entries by email Archives

February 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed